Connor Boyle

Find me on:

Posts:

Rep. Paul Gosar's Claims about OPT Contain Major Errors

by Connor Boyle

tags: politicsimmigration

U.S. Congressional Representative Paul Gosar of Arizona1 recently reintroduced proposed legislation to ban the Optional Practical Training program (OPT).2 OPT is a program that allows international students attending college & grad school to legally remain in the United States and work in their field of study for 1 year after completing their degrees.3 Students majoring in an approved science, technology, engineering, and/or math (STEM) field are eligible to apply for a 2-year extension at the end of their initial 1-year OPT periods.

As a former volunteer at my alma mater’s international student program, I happen to have some knowledge about OPT and the policies concerning student (F-1) visa holders that led me to suspect there were major errors in Paul Gosar’s statement regarding the bill, as well as in the articles from advocacy groups that he cites. In addition to some superficial and obvious errors, such as claiming that OPT was “expanded by three years by the Obama Administration” (it was in fact expanded only by seven months), Gosar’s post claims that:

These foreign workers are exempt from payroll taxes[,] making them at least 10-15 percent [sic] cheaper than a comparable American worker. NumbersUSA reports OPT costs the Social Security and Medicare trust fund [sic] $4 billion annually.

The document from NumbersUSA (an immigration restrictionist advocacy group) cites a 2024 article from the Center for Immigration Studies (CIS, another restrictionist group), which in turn simply scales up an earlier estimate from a 2015 CIS article.

The author of the 2015 article, David North, tallies the number of OPT & OPT STEM extension approvals, then multiplies by 12 or 17 months respectively (the STEM extension was only 17 months long at the time) to determine the number of years an OPT worker will have worked in the United States without being liable for Social Security and Medicare taxes. He proposes an estimated average OPT salary based on that of the average college graduate, and estimates the total loss to Social Security & Medicare like so:

\[(\textrm{FICA-exempt worker-years}) \cdot (\textrm{avg. salary}) \cdot (\textrm{total FICA rate}) = \textrm{total loss to Soc. Sec. & Medicare}\] \[= \textrm{524,021 years} \cdot $\textrm{50,000/yr.} \cdot 15.3\% = \textrm{\$4,008,760,600}\]Many OPT Workers do in Fact Pay FICA

There are a few problems with this estimate, but I will start with the most glaring one: it is not true that all or even nearly all post-completion OPT workers (and their employers) are exempt from FICA. The reason that some OPT workers are exempt from FICA is that they are nonresident aliens. And while F-1 student visa holders (including OPT workers) are always considered nonresident aliens for immigration purposes, they are only treated as such for tax purposes until they pass the “substantial presence” test.4

The “substantial presence” test is rather complicated, but in a typical case, an international student will not be considered substantially present for their first 5 calendar years in the United States, due to a policy exempting F-1 visa holders for that period. The visa holder will usually come to be considered “substantially present”—assuming they spend a majority of that year in the United States—beginning January 1st of their 6th calendar year in the United States. The visa holder is then treated as a resident alien for tax purposes and is thus subject to the payroll taxes funding Social Security & Medicare, a.k.a. FICA. The only likely way for an international student not to be considered a resident alien is if they spend fewer than 183 days in the United States in their final calendar year in the United States.

Substantial presence is not some niche exception; it ultimately applies to a very large number—perhaps a majority—of post-completion OPT workers at some point in their OPT period. Keep in mind that degree programs are generally mis-aligned to calendar years and therefore push F-1 holders/OPT workers into resident alien tax status sooner than if they weren’t.5

| Degree type | Typical length | Max Yrs. as NRA post-completion (STEM / non-STEM) | Explanation | Exceptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bachelor’s (B.A. / B.S.) | 4 years | 0.5 / 0.5 | Degree completed in 5th calendar year, likely begins post-completion OPT in June or July. Resident alien tax status kicks in January of the following calendar year | If the OPT worker leaves the US before early July of the following year, they will remain a nonresident alien for tax purposes |

| Master’s (M.A. / M.S.) | 2 years | 2.5 / 1 | Degree completed in 3rd calendar year; resident alien tax status kicks in January 1 of 6th calendar year, roughly two and a half years after completion | Many master’s students were previously bachelor’s students in the US and thus would have 0 years of nonresident alien tax status post-completion |

| Law (J.D.) | 3 years | N.A. / 1 | Degree completed in 4th calendar year; resident alien tax status would kick in January 1 of 6th calendar year, roughly two and a half years after completion; however, law students do not qualify for the STEM extension | Many law students were previously bachelor’s students in the US and thus would have 0 years of nonresident alien tax status post-completion |

| Doctorate (Ph.D.) | 5+ years | 0 / 0 | Degree completed in 6th calendar year (optimistic for many fields); resident alien tax status kicks in during last year of degree (or sooner, if the student had previously studied in the US) |

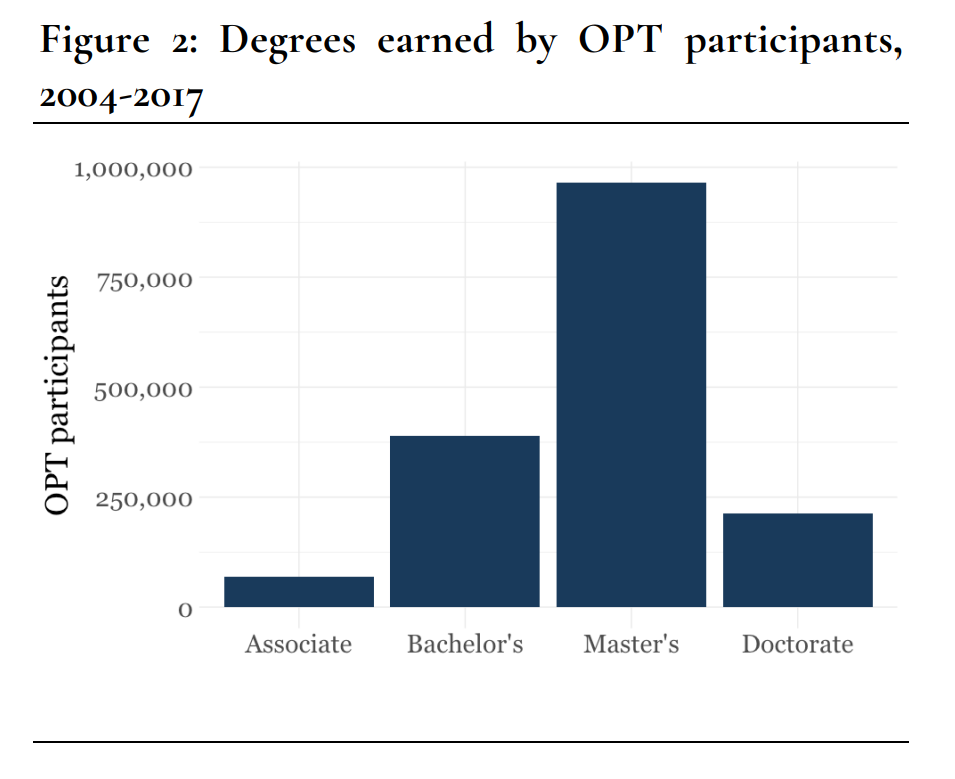

Unfortunately, I couldn’t seem to find public reporting from ICE or USCIS to break down the share of OPT participants by level of degree attained. However, based on this report from the Niskanen center, which obtained additional statistics on OPT educational attainment levels via a FOIA request, we can see the different levels of education attained by OPT workers:

I have attempted to combine the Niskanen data, official ICE-reported numbers on OPT & OPT STEM extension approvals in 2022, and no small number of naïve and arbitrary assumptions6 to estimate the total number of years worked by post-completion OPT workers as nonresident aliens (NRAs) vs. as resident aliens (RAs) for tax purposes.

I estimated that in 2022, a narrow majority—about 53%—of all post-completion OPT time was worked while in resident alien status. In other words, if this estimate is accurate, most OPT workers and their employers at any given time are paying into the Social Security and Medicare trust funds at exactly the same rate as a US citizen and their employer would be. This estimate comes with much uncertainty; the result can shift quite dramatically depending on how many master’s graduates we assume to be substantially present by the time of graduation. That said, I think this estimation is useful as an exercise showing how complicated it is to estimate the amount of FICA paid by OPT workers, as well as a demonstration of the magnitude of CIS, NumbersUSA, and Paul Gosar’s error.

Nonresident Alien Tax Status is not Always Advantageous

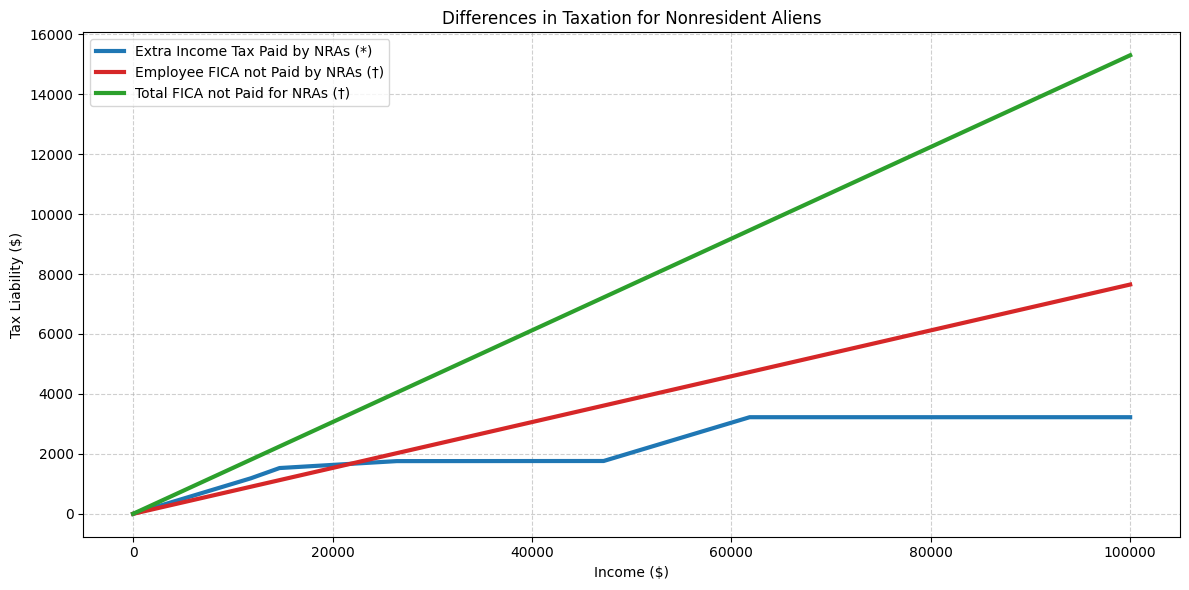

Excepting FICA exemption, nonresident alien status generally leads to a higher tax burden. Nonresident aliens other than Indian residents7 cannot take the standard deduction, and almost no nonresident aliens8 can take the earned income tax credit, the American opportunity tax credit, the lifetime learning credit, or many other deductions and credits that an American worker would be able to take.

In the above chart I have plotted the additional tax burden caused by a lack of standard deduction compared to the tax burden avoided by being exempt from FICA.9 Note that the lower one’s income, the less of a tax advantage one is conferred by nonresident alien status. At income levels of around $20,000 or less, more than the entire employee FICA advantage for NRAs is wiped out by the increased tax burden due to a lack of standard deduction. You may think it unlikely that a post-completion OPT worker would make only $20,000 (or less) in a year; if so, I think you would be correct (see next section).

However, many international students likely earn wages in this range when they work on-campus while enrolled as a student. International students (like their domestic peers) can take part-time jobs at their home institutions, often helping to run facilities such as libraries and cafeterias or serving as teaching assistants (or even instructors, in the case of PhD students). In the case of these student workers, nonresident alien status loses its main advantage (that is, FICA exemption), because all student workers at colleges and universities—including U.S. citizens—are universally exempt from FICA. In other words, F-1 student visa holders are most likely to have nonresident alien status precisely when it is least advantageous, often increasing their total tax burden relative to a US citizen’s.

I would like to pause very briefly to bring up just how unfair the tax treatment of international students can be. Nonresident aliens are excluded from paying FICA for a specific reason—FICA specifically funds social insurance programs that most nonresident aliens will never be able to collect from (granted, this logic doesn’t particularly apply to their employers). What is the justification for why we take an extra 10% out of the wages of an international student paying their way through college by washing dishes in the cafeteria? If anyone can tell me a good reason, I’m all ears, but until then I’ll assume it’s nothing more nor less than “because we can”.

OPT Workers are Probably Paid Much More than the Average New College Graduate

In CIS’s 2015 estimate of lost FICA income due to OPT workers, author David North estimates the average income of an OPT worker as $50,000 per year, based on a 2011 report showing the average new college grad salary as $50,034.10 I’m a bit surprised he didn’t try to find a newer estimate or at least adjust for general wage growth, as this would have allowed him to claim that OPT was depriving Social Security and Medicare of an even larger amount of money.

On the other hand, I think this would contradict a larger narrative that Rep. Gosar and CIS seem to believe about OPT. Namely, they assert that OPT is fundamentally a sham program to funnel “inexpensive foreign labor” (in Paul Gosar’s words) into American jobs. Listening to immigration restrictionists, you’d get the impression that the average OPT worker has “graduated” from some fly-by-night for-profit diploma-cum-visa mill, or at best an un-selective associate’s degree program, in order to exploit the OPT “loophole” with their sham degree and work in some low-skill job with no real connection to their supposed field of study. As David North wrote for CIS in 2018, “many a pizza place is staffed with OPT workers”.

This certainly does not resemble the experiences of my international classmates at Macalester College, who often out-earned me at renowned firms such as Google, Ernst & Young, or Merck, to name a few. But perhaps my view from a selective liberal arts college is not representative of the typical OPT worker and their career. This spreadsheet published by ICE showing the top schools for active OPT records in 2022 might give us some insight into what kind of new college and university graduates are participating in OPT. Here are the top 20 schools:

| # | Campus Name | Graduates Employed through OPT |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Northeastern University | 4,593 |

| 2 | Columbia University | 4,127 |

| 3 | University of Southern California | 3,520 |

| 4 | New York University | 2,996 |

| 5 | Arizona State University | 2,663 |

| 6 | University of California at Berkeley | 2,363 |

| 7 | Carnegie Mellon University | 2,134 |

| 8 | The University of Texas at Dallas | 2,096 |

| 9 | Boston University | 2,017 |

| 10 | University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign | 1,996 |

| 11 | The University of Texas at Arlington | 1,894 |

| 12 | Purdue University | 1,797 |

| 13 | University of Washington - Seattle | 1,758 |

| 14 | State University of New York at Buffalo | 1,754 |

| 15 | University of California San Diego | 1,673 |

| 16 | University of Michigan - Ann Arbor | 1,635 |

| 17 | University of California, Los Angeles | 1,620 |

| 18 | University of Pennsylvania | 1,553 |

| 19 | Harvard University | 1,497 |

| 20 | Georgia Institute of Technology | 1,469 |

| … | … | |

| Total for Top 100 Schools | 106,060 | |

| Full Total (*2022) | 171,635 |

Not only are these schools reputable, legitimate institutions of higher learning, many of them are the most prestigious universities in the entire world!11 The top 100 schools for OPT authorizations includes almost the entire Ivy League (with the exceptions of Dartmouth and Princeton), Stanford, MIT, Duke, Johns Hopkins, and the University of Chicago. This is remarkable, considering that these exceptionally prestigious schools are generally not particularly large; for example, Harvard’s total enrollment of 21,278 is smaller than that of 11 California State University campuses, only 1 of which is among the top 100 OPT schools.

Using data on the top schools for OPT authorizations in 2022, I compared several schools’ share of all degrees awarded to their share of OPT workers. In that year, compared to the general population of new bachelor’s degree recipients, an OPT authorization recipient was:

- over 7 times as likely to have graduated from Stanford,

- over 11 times as likely to have graduated from MIT, and

- over 13 times as likely to have graduated from Harvard

this discrepancy is due in part to the fact that these institutions grant far more master’s degrees compared to similarly-sized institutions. However, even comparing to the average master’s recipient, an OPT worker is:

- 2.23 times as likely to have graduated from Stanford,

- 2.77 times as likely to have graduated from MIT, and

- 1.92 times as likely to have graduated from Harvard

Sources such as this article from the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank, as well as common sense, tell us that graduates of more selective universities tend to significantly out-earn graduates of less selective institutions. We also know that most OPT recipients are master’s degree holders; according to this report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, master’s degree holders out-earned bachelor’s degree holders by 15% in 2022. Contrary to Paul Gosar’s description of OPT workers as “inexpensive foreign labor”, I suspect that OPT workers significantly out-earn the average new college graduate.

Gosar et al.’s Assumptions about Employment are Likely Wrong

Representative Gosar, NumbersUSA, and CIS seem to assume that OPT workers’ only impact on the U.S. economy is to take jobs away from U.S. citizens and green card holders who could have worked these jobs and now must be unemployed as a result. In their counterfactual analysis, these critics of OPT don’t consider the possibility that the quantity and quality of labor available could itself influence the rate of formation, expansion, or closure for firms. They also don’t consider that the quantity and quality of labor available could affect the quality and price of goods & services, and by extension the real incomes of U.S. citizens. They do not entertain the possibility that some of the jobs worked by OPT workers could have otherwise been outsourced, taken by a foreign competitor, or simply gone unfilled. Nevermind that many former international students have founded multi-billion dollar companies that employ many thousands of U.S. citizens.

There is a large body of economics research analyzing the effects of skilled immigration on the US economy and workers. I am not by any means an expert in economics, however, The University of Chicago, itself home to one of the most highly-regarded economics departments in the world, conducts polls of economists on various economics questions. For example, on the question of whether reducing the number of H-1(b) visas would increase employment opportunities for American workers, 45% of polled economists responded “disagree”, 36% responded “strongly disagree”, and 19% responded “uncertain”; 0% of economists responded “agree” or “strongly agree”. Put differently, the field of economics generally believes that H-1(b)—a program that allows foreign skilled workers similar to those in OPT to work temporarily in the United States—does not significantly negatively impact the employment prospects of American workers.

I would be interested to see whether these experts feel similarly about OPT as they do H-1(b); if so (and if they are not all wrong), then each OPT worker may in fact not be simply displacing an American worker, but instead adding new value to the American economy that wouldn’t have existed otherwise. In that case, I think it is only fair to consider some share of the FICA paid by OPT workers to be a net gain relative to the counterfactual in which those OPT workers were not allowed to work in the United States. Rather than depriving Social Security & Medicare of badly needed funds, OPT workers may be contributing more than would otherwise be present.

This paper, which studies the effects of the random lottery for H-1(b) visas on firms, estimates that each H-1(b) lottery win for a firm increase that firm’s total employment by 0.83. This is only a firm-level estimate; the effect on total employment in the United States economy may be greater or lesser than this number.

Out of a desire to estimate the net effect of OPT on the Social Security & Medicare trust funds, I’ll split the difference between:

- Rep. Gosar, CIS, and NumbersUSA, who implicitly assume that each OPT worker adds roughly 0 new employment to the United States, and

- the 42 expert economists polled by the University of Chicago, who seem to think that each skilled worker (in their case, in the H-1(b) program) adds approximately 1 (or more) total comparably-employed workers to the United States economy.

therefore, I will assume that each OPT worker only increases total employment (comparable in compensation to the job worked by an OPT worker) in the United States by 0.5. Put differently, I’ll suppose, for the sake of estimation, that OPT workers really do displace American workers (for the duration of their OPT periods), but because a) they increase firm profitability b) lower the cost of goods & services to American consumers, and c) work some jobs that may have otherwise gone unfilled or taken by a foreign competitor, they generate enough additional economic value in the U.S. that the number of displaced workers is only half of the number OPT workers.

Conclusion

To estimate the net gain or loss to the Social Security and Medicare trust funds, we must compare the reality of the US with OPT workers to the counterfactual without OPT workers. First, the FICA revenue generated in reality by OPT workers (directly or indirectly):

\[(\textrm{OPT}_{RA} + \textrm{OPT}_{total} \cdot \textrm{NewEmployment}) \cdot \textrm{AvgSalary} \cdot \textrm{FICA}\]minus the counterfactual (in which OPT does not exist):

\[\textrm{OPT}_{total} \cdot \textrm{AvgSalary} \cdot \textrm{FICA}\]where:

- \(\textrm{OPT}_{total}\) is the total number of OPT worker-years

- \(\textrm{OPT}_{RA}, \textrm{OPT}_{NRA}\) is the number of OPT worker-years spent in resident or nonresident alien status, respectively

- \(\textrm{NewEmployment}\) is the total (worker-years of) employment added to the US economy by each worker-year of OPT

- \(\textrm{AvgSalary}\) is the average salary of OPT workers

- \(\textrm{FICA}\) is the total FICA rate (employer- and employee-)

Subtracting reality from the counterfactual gives us:

\[(\textrm{OPT}_{RA} + \textrm{OPT}_{total} \cdot \textrm{NewEmployment} - \textrm{OPT}_{total}) \cdot \textrm{AvgSalary} \cdot \textrm{FICA}\] \[= (\textrm{OPT}_{total} \cdot \textrm{NewEmployment} - \textrm{OPT}_{NRA}) \cdot \textrm{AvgSalary} \cdot \textrm{FICA}\]Now I’ll substitute the values we estimated earlier. This report from the National Association of Colleges and Employers says that new bachelor’s graduates in 2022 took home a median starting salary of $60,028. To give a very rough estimate of the salary of OPT workers (who, on average, are master’s degree holders), I’ll increase that by 15%, to get an average salary of $69,032.20.12

\[= (\textrm{246,989 worker-years} \cdot 0.5 - \textrm{115,508 worker-years}) \cdot \textrm{\$69,032.20} \cdot \textrm{15.3%}\] \[= \textrm{7,686.5 worker-years} \cdot \textrm{15.3%} \cdot \textrm{\$69,032.20}\] \[= \textrm{\$81,184,248.81}\]I estimate that the total net gain to the Social Security & Medicare trust funds due to the existence of OPT could be $81,184,248.81. I don’t expect anyone to take this estimate too seriously; I had to make arbitrary guesses for many very important values.6

That said, this estimate is at least as valid as that of CIS, which through a chain of blindly trusting references, ended up being cited by a member of United States Congress as if it were fact—despite a blatant error, which could easily have been revealed by anyone through a simple web search.

OPT workers are by and large graduates of quite selective colleges and universities, who in fact do contribute significantly to American social insurance programs from which they ultimately might never collect. Even from the most self-interested, nationalist perspective, these are among the most desirable people in the world to have in any country. When I read Paul Gosar describe OPT workers—which many of my closest friends have been at one time or another—as “cheap foreigners”, I was more than a little insulted on their behalf. I hope this blog post serves to correct the record. Most OPT workers are anything but cheap, low-quality labor incentivized by unfair tax breaks; they are some of the best and brightest of our workforce.

Rather than making yet another futile attempt to eliminate the OPT program, I would suggest that Congressman Gosar instead propose legislation to reduce or eliminate the time (currently 5 calendar years) that F-1 student visa holders are exempt from the substantial presence test. If the years of exemption were eliminated entirely, this would cause virtually all OPT workers to be subject to FICA for the entirety of their OPT periods, making international students contribute even more to the coffers of Social Security and Medicare than they already do. However, this would come at a cost to the United States Treasury, increasing our national deficit, as international student workers would then be able to take credits and deductions otherwise denied to them.

Addendum: No Minor Blunder

David North, the author of the 2015 CIS article providing the original framework for estimating FICA revenue supposedly lost to OPT, writes that he volunteered to help graduate students—including international students—file their taxes. And yet, he writes:

The assumption is that all these years of tax-free status were used; in reality, probably a small fraction of the tax-free status was not used because the recent graduate either moved on to another visa category, left the nation, or, in a very few cases, died.

North gives no indication that a typical OPT worker would, in fact, be fully liable for FICA for a significant share (possibly most or all) of their OPT time. I’m tempted to presume that he knew how many OPT workers used OPT after getting master’s degrees, which in some cases could allow them to be FICA-exempt for nearly the entirety of 1-year OPT and a STEM extension (assuming they did not get their bachelor’s degrees in the US, too). However, he specifically uses the average salary of new college graduates as the estimated salary of OPT workers, indicating he assumes they are primarily bachelor’s degree holders.

This is no small blunder! Determining tax residency is literally the first (and probably most important) step in filing taxes as a noncitizen. It determines whether the noncitizen filer can submit a normal form 1040 (resident) or 1040-NR (nonresident) as well as which tax filing software the filer can use (e.g. TurboTax vs. Sprintax). So either:

- North was woefully incompetent to assist any noncitizen living in the U.S. with their taxes, possibly causing them to file completely incorrectly

- North lied about having helped international students with their taxes, or

- North knew that many OPT workers would not be exempt from FICA, but intentionally lied to his readers by writing that nearly all OPT workers are exempt from FICA

What’s more, North did not just make this misrepresentation in a blog post (that was ultimately read and cited by a member of the United States Congress), he made this same claim in an amicus brief submitted to a federal court in 2019!13 This level of carelessness from a professional think-tank writer who had written well over a dozen articles on this topic before submitting this amicus brief is remarkable, especially considering this information was easily available to the public on the IRS website as early as 2013.

Thank you to my friend Stephanie Hou, who helped to proofread this post. Any mistakes are my own.

Footnotes:

-

In an earlier version of this post, I mistakenly wrote that Paul Gosar is the representative from Nebraska instead of Arizona. A friend helpfully pointed out this error to me. ↩

-

I will mostly discuss post-completion OPT in this post, since post-completion OPT seems to specifically be the part of the program that Paul Gosar and other restrictionists criticize, as opposed to pre-completion OPT or Curricular Practical Training (CPT). ↩

-

F-1 visa holders can (and often do) pick a start date for their post-completion OPT period as late as sixty (60) days after the end of their program. The OPT work permit lasts for 365 days, and, assuming the student maintains valid employment for the entire period, ends with a 60-day grace period where the student cannot work but can legally remain in the United States. ↩

-

The “substantial presence” test has an exception: the “closer connection” test (TODO: write more about this and why it’s unlikely to apply to OPT holders) ↩

-

Many international students set their OPT start date as late as possible; they can set it up to 60 days after their graduation. They do this for two reasons:

- USCIS can be very slow to process OPT applications, taking 90-120 days in some cases (note that F-1 visa holders can only apply at most 90 days in advance of graduation!!). A late start date ensures that the OPT worker maximizes their allowed work time and none is spent waiting for approval.

- Once their OPT period starts, F-1 visa holders can only be unemployed for a maximum of 90 days (although the STEM extension adds 60 unemployment days) before they will be marked out-of-status and be required to leave the country; since students have to set their OPT start date when they apply, they often set it late to ensure they will be able to find a job before their allowed unemployment time runs out.

-

I made the following assumptions when calculating post-completion OPT time in RA vs. NRA tax status:

- that the share of degrees represented in OPT approvals in 2022 was identical to that in the 2004-2017 period

- that no OPT workers finished their degrees early or late

- that no bachelor’s degree OPT workers had previously studied or lived in the United States

- that 25% (an arbitrary figure that sounded plausible to me) of master’s degree holders had completed their bachelor’s degree in the US or would otherwise be considered substantially present by the time of graduation

- that master’s degrees take 2 years

- that all OPT workers completed their entire OPT (and STEM extension if so approved) without early termination or moving to another visa type (e.g. H-1b)

- that OPT STEM extensions are proportionately distributed among degree levels (excluding associate’s degrees, for which the STEM extension is not allowed)

-

Indian residents are allowed to take the standard deduction even when they are nonresident aliens (for tax purposes) due to a tax treaty between the United States and Inida. Some other countries have tax treaties as well, such as China, whose residents can take a deduction of $5,000 (while in NRA tax status), compared to the standard deduction of $14,650 for single filers in 2024. See Sprintax for more examples. ↩

-

For example, if a married couple, one of whom is a U.S. resident and one is not (for tax purposes), files jointly, the nonresident spouse can choose to be treated as a resident for tax purposes. ↩

-

The extra tax burden paid by nonresident aliens due to not being able to take the standard deduction and other deductions and tax credits is paid to the U.S. treasury, rather than to the Social Security and Medicare trust funds, as would be the case with FICA. This is a distinction without a difference in my opinion. ↩

-

In Jon Feere’s 2024 estimate he continues to use this figure ($50,000 / year) as the estimated wage for OPT workers. I’m particularly baffled by him continuing to use this decade-old number, especially since it would help his argument to update it! Inflation alone from 2015 to 2024 was 35%—average wages for new college graduates must have changed a lot, too! ↩

-

While the full “top 100” list contains overwhelmingly reputable institutions, I would say that at least one, possibly two, schools on the list do not quite fit most people’s idea of an ideal institution of higher learning. That said, the inclusion of these unorthodox schools doesn’t change the more important point: that OPT is very disproportionately used by graduates of the most prestigious schools in America. ↩

-

I believe $69,032.20 / year for the average OPT worker may still be an underestimate because: 1) we want the mean, not the median, and 2) it does not account for the more selective schools and higher-earning majors that OPT workers disproportionately choose. ↩

-

In the amicus brief, not only does North misrepresent the exemption from FICA as being universal for OPT workers, he also seems to misattribute the reason for the exemption. He conflates the F-1 “substantial presence” exception (the real reason why some OPT workers are exempt from FICA) with the “student” exemption to FICA, which only applies to students working at their home institution where they are currently enrolled full-time. In this later post from 2023, he seems to recognize that OPT workers’ exemption from FICA stems from their nonresident status due to exemption from the substantial presence test. ↩